Rudi Bekaert defines himself as “an amused observer”. One of few Belgian authors following the tradition of being able to write equally well in two languages, he wrote Ja Ja maar nee nee and Ah oui ça alors là in 1997, acted alternately in Dutch and French by members of Dito’Dito and transquinquennal. In it he delighted in reproducing the malicious gossip of the residents of a block of council flats. Now he has recorded the intimate chatter of the upper- middle classes. Kortom (in Dutch) and Enfin Bref (in French) are ‘plays about impunity’, according to the Brussels actors who themselves perform their encounter as a form of listening.

“After Ja Ja maar nee nee and Ah oui ça alors là, which was about working-class people, I wanted to write about the well-to-do bourgeoisie”, Rudi Bekaert explains. “The fact that it is such a closed circle gave me inspiration. I was intrigued and inspired by the world of these people who do the social rounds of fashionable cocktail parties. There was one I went to where I was introduced to the guests and told, ‘I’d like to introduce you to Monsieur So-and-So. And this is Madame So-and-So who is the wife of Such-and-Such, the famous lawyer’, when I was introduced with an offhand ‘Anyway…(Enfin bref)’. This became the title of a play that had been going round in my head. I wanted to write about people who think nothing of spending BF 150,000 a month for a villa in Knokke-le-Zoute and BF 2 million a month on their day-to-day needs. Nothing shocks me about it because things are so excessive nowadays. But I am often offended, I think, and upset by it. I feel responsible for the dramas I witness taking place. I try to incorporate it into my writing. I don’t write moral plays. I don’t know what that is. I hear, I listen, I take note, and then I write. I’m an amused observer.”

Ja ja maar nee nee and Ah oui ça alors là were created in October 1997 in Dutch- and French-language at De Markten. Ah oui ça alors là, the French version, was then performed at the Théâtre de la Balsamine in Brussels, with a month at the Théâtre de la Cité Internationale in Paris and is scheduled this season for the large auditorium at the Théâtre National. Both versions have been big hits. All the action takes place in an enclosed environment – the entrance hall of a block of council flats. It has become a place where the residents gossip and discuss their tiniest concern. They hold forth on their views of social problems, show reassuring solidarity on issues and share their common disapproval of things. They enjoy blowing things out of all proportion. Rudi Bekaert assembled a whole range of those little instinctive, basic phrases which humorously bring out everyday racism, the things people mistrust, blatant hypocrisies, bits of malicious gossip, the inquisitiveness of busybodies and their own high opinions of themselves. It was delicate, savage, light, impertinent and extremely intelligent.

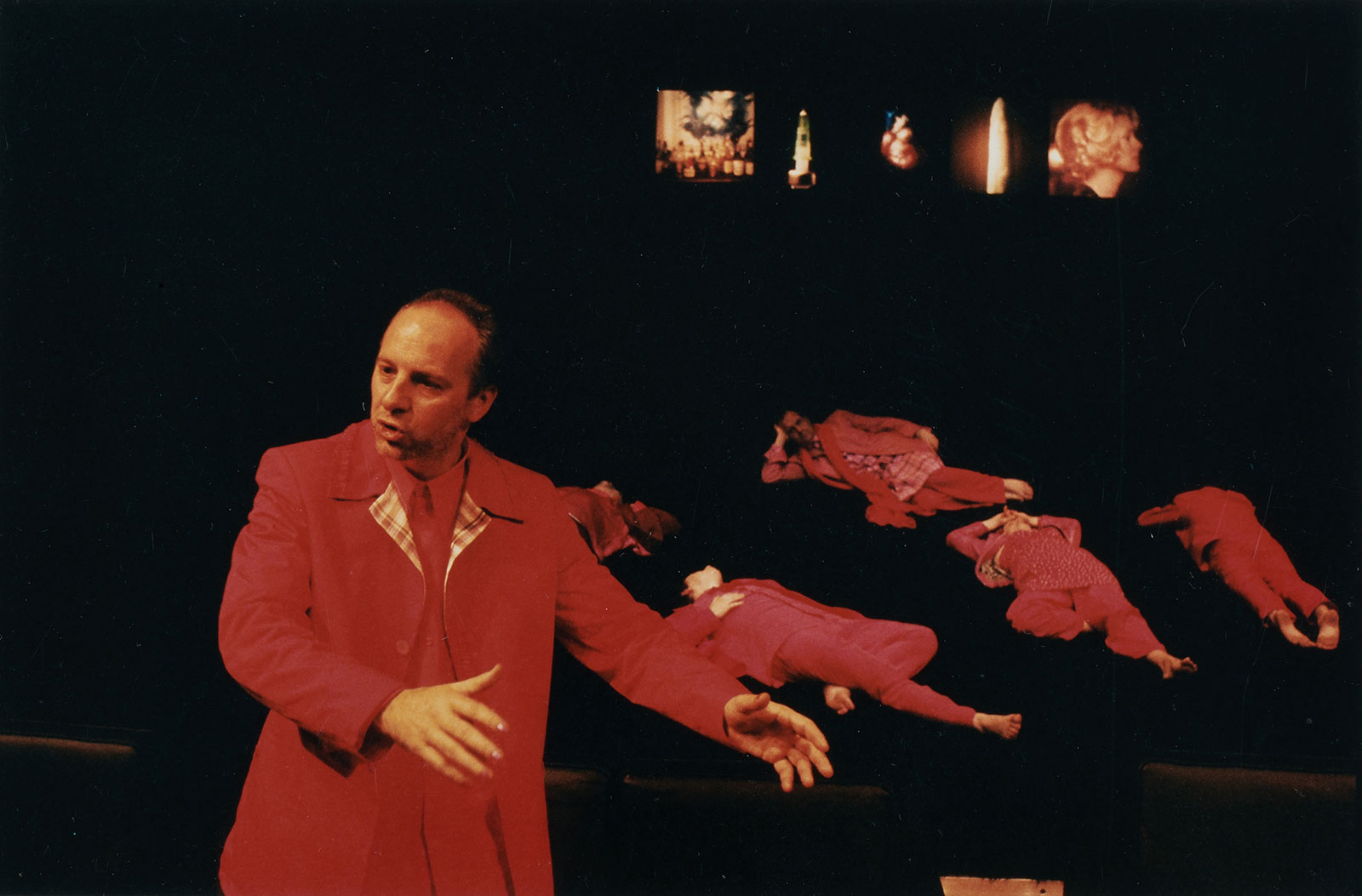

Rudi has now created Enfin bref in French and Kortom in Dutch, performed in their respective languages by Dito’Dito and transquinquennal. The play comprises 30 scenes, of which more than a third are monologues. With an inexorable symmetry, fifteen of them take place in the grand villa belonging to the Ickxs, the other fifteen in the equally sumptuous villa belonging to the Bertin family. It is a world where mobile phones abound, whisky flows liberally, the Café Nemrod in the Avenue de la Toison d’Or is the place to be and where its citizens exchange upmarket gossip, problems with jewellery and New Age therapies. It explores the hectic environment of a jet set that wants for nothing – except that they lack everything.

Enfin bref will be followed by another work, Vanzelfsprekend (That goes without saying), a rural comedy about country life. There are not many contemporary ‘bourgeois’ dramas written anymore, but there were plenty at the end of the nineteenth century, offering those who had recently arrived at that level of society a mirror of their own failings. With access to theatre democratised in the twentieth century, theatre became more interested in the less privileged, before having to redefine itself following the popularity of cinema and then television. It became more radical in its forms, explored new ways of relating stories and took the time to seek out the absurd in the human condition. That is why a play like Rudi Bekaert’s is disconcerting. Is it like a Belgian Dallas? The difference is that there is no intrigue for power, no nasty JR, no family saga, no war and no peace. The Ickxs, Bertins and the rest of them make money. They have it in their power to own everything. But how should they be when they can have so much? In these two classy interiors, the businessmen are hardly there whilst the women fuss over bills for jewellery, exotic safaris, Prozac, sunbeds and garden parties.

Stéphane Olivier says, “Rudi doesn’t teach us anything about these people. When it comes down to it, they even seem to be talking in clichés. But it is reality. Rudi wants us to listen to what reaches our ears every day without really making any impression on us. It’s as if he feels that he has to repeat things so that they can be heard. His play is attacking something very serious in our society – the impunity that power brings. That’s its content. For the form, his writing places the actor opposite the audience in the same position of ‘having’ that the characters have. We each have to manage monologues of around three pages long. That gives us great power! There is no linear structure to the text; his scenes are almost all completely interchangeable. On the other hand, the characters are unaffected by time. At least that’s what they think. Distance doesn’t matter either, because you can reach anywhere by jumbo jet and the mobile never stops ringing. None of them really listens to anyone else.”

Rudi Bekaert says, “It would be good to put up a sign at the entrance to the auditorium saying, Please do not switch off your mobile phone during the performance. You are also especially requested not to put it on pulse mode. If it rings, please answer it.”

According to Mieke Verdin, “In Ja ja maar nee nee, people still had to take the lift to meet up and be able to talk to each other. Any old topic became a subject for debate. Here, no one picks up on the information the previous person gave them. Everyone seems to speak alone when they have every means of communication at their disposal. They have everything, but are taken over by vacuousness. The play appears to be harder and less humane than Ja ja maar nee nee and Ah oui ça alors là. Maybe it’s because we forgive the poor more than we do the rich. But does Xandra in Enfin bref have more ‘human’ power than Madame Vandeputte in Ja ja maar nee nee? We are not really interested in critiquing an environment, but we question human relationships, the impotence of existence and unconscious cruelty.”

Rudi Bekaert ends by saying: « Enfin bref was easier to write in French than Kortom was in Dutch. For the Dutch version I had to recreate the language. Historically, the upper classes in Belgium pride themselves on speaking French with its formal ‘vous’ and elegant constructions. The Flemish bourgeoisie today can’t be distinguished by their language. It makes a difference in form, but not in content.»

Read more

Hide

Credits

“Kortom” and “Enfin bref” are the same pièce. "Kortom" is the Dutch translation of "Enfin Bref".

Collective direction

Distribution : Bernard Breuse, Guy Dermul, Stéphane Olivier, Pierre Sartenaer, Willy Thomas, Mieke Verdin

Stage, lights, technical direction : Bart Luypaert

Construction of the stage : Ralf Nonn, Piet De Koster

Costumes : Lies Van Assche

Slides : Mirjam Devriendt

Music : Dett Peyskens, Curd Duca

Voice : Gordon Wilson

Photos : Hans Roels (terrain de golf), Herman Sorgeloos

Flyer : Bart Luypaert

Organisation : Manu Devriendt, Anne Vanderschueren

Production : Dito Dito & Transquinquennal

Coproduction : KunstenFESTIVALdesArts, Théâtre National de la communauté Wallonie-Bruxelles

Copresentation : KunstenFESTIVALdesArts, Théâtre National de la communauté Wallonie-Bruxelles

With the support of : Vlaamse Gemeenschap Administratie Cultuur, Vlaamse Gemeesschapcommissie van het Brussels Hoofdstedelijk and la Loterie Nationale